Christophe Lebold, who has written the definitive biography of the great singer- songwriter Leonard Cohen told David Hennessy how he got his love for Ireland from his Irish nanny, his love of Yeats and getting to spend time with him before he passed.

Leonard Cohen had a love affair with Ireland.

The legendary singer-songwriter and poet performed at many of the country’s venues including Belfast’s Odyssey Arena and the O2 Arena and the National Stadium.

One of his final albums was entitled Live in Dublin and he was even known to sing the Irish ballad, Kevin Barry in concert.

Leonard remarked, “When I think of Ireland I think immediately of words and language as well as spirituality.”

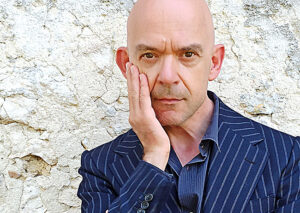

The Irish World spoke to University of Strasbourg associate professor Christophe Lebold about his biography Leonard Cohen – The Man Who Saw the Angels Fall which received its first English release recently.

The new biography, which was first released in French in 2013, has been described as the definitive memoir of one of the most important poets and songwriters of our times.

Writer Christophe Lebold spent twenty years researching his subject and grew close to Leonard spending time with him in Los Angeles not long before he died in 2016.

Legendary singer-songwriter and poet Leonard Cohen, who would have turned 90 this year, penned Sisters of Mercy, So Long, Marianne, Bird on the Wire, Suzanne and his signature song Hallelujah.

Hallelujah has been covered by the likes of Jeff Buckley, Bon Jovi, Bono, Rufus Wainwright, Bob Dylan, John Cale, Susan Boyle and Alexandra Burke.

According to Bono the 1984 track is “the most perfect song in the world”.

Sir Elton John described the influential Montreal-born novelist/ songwriter as “a giant of a man and a brilliant songwriter” while Bob Dylan called him a “genius”.

Let’s go right back to the beginning, do you remember when your passion for Leonard Cohen started?

“Yeah, I remember very well.

“I was 14 and there were two events.

“One is my father took out two LPS that he bought the year I was born, that’s 1974 and the two LPS were Leonard Cohen’s Greatest Hits.

“It had Suzanne, Stranger Song, Who by Fire: Great classics.

“And the other one was New Skin for the Old Ceremony, also by Leonard Cohen, and I immediately liked it.

“I felt a calling or a pull.

“I was struck by the poetry.

“I remember I was trying to read Shakespeare at the time.

“It was very, very hard and here was a poet I could understand.

“And the same year it was Leonard Cohen’s first great comeback with the album I’m Your Man.

“I remember my father telling me it’s the same guy.

“I thought, ‘No, it can’t be the same guy’.

“And this is how it began.

“I discovered a couple of years later that he was also a poet and a novelist.

“I remember buying the first two novels, The Favourite Game and Beautiful Losers.

“So later when I was at university and they asked me, ‘Do you want to write a dissertation on something?’

“I said, ‘Yeah, I want to write a dissertation on Beautiful Losers’.

“That’s how we began.

“I remember it took me maybe seven or eight years to get all the records so it was like gradually moving into the water of Leonard Cohen and the water getting higher and higher.

“I remember getting a feel of what this universe was like.

“It seemed completely familiar, his fictional universe, people waiting for salvation in hotel rooms, a woman falling in love with fire, a man stepping into an avalanche.

“All of this seemed like pure realism to me.

“I thought, ‘At last I’ve found a realistic author, someone who describes life as it is’.

“And I loved the voice. It really spoke to me.

“I was in my late teens so I was looking for heroes.

“Certainly Leonard was one.”

So you wrote your dissertation and decided to reach out to him, not expecting to hear back but lo and behold, Leonard Cohen himself did get back to you and you became friends eventually…

“Yeah, we did.

“It’s a really nice story.

“I always tell my students, ‘Never give up on a project. Always reach out. You never know what’s going to happen. You might get lucky’.

“Strangely enough maybe two months later, I just happened to be opening my email box and I could see ‘from Leonard Cohen’,

“I fell off my chair.

“He wrote a very moving message saying how much he appreciated it.

“So then we started writing each other.

“But after a while, it got more personal especially after we met during the 2009 tour.

“We met in the street in Liverpool.

“I was in Liverpool for another reason but there happened to be a Leonard Cohen concert.

“I was on the dock, looked up and Leonard Cohen was walking three metres away from me.

“I said, ‘Leonard, Leonard. It’s me, Christophe’.

“We shook hands, we talked for three minutes. He was lovely and he said, ‘We gotta carry on by mail’.

“Then the first edition of the book was published in 2013 in French and he really liked that.

“I had translated little bits of it for him and he said, ‘Well, we should meet now. Come to my place’.

“And this is when I spent time with him in Los Angeles but what is great is that it took so long for us to be in the same room so we felt we knew each other already.

“He felt he knew me because we had been writing to each other for a few years.

“He was the humblest man that you can possibly imagine he was.

“If you were nervous when you met him, after a couple of minutes, that nervousness dissolves because he was so courteous, so down to earth, so graceful actually, that he made it seem completely painless and then he was very generous.

“Immediately we were talking like old buddies.”

Was the surprise in meeting him that he was so humble? “No, I kind of expected that really because I had seen him on stage a few times.

“He created this level of intimacy onstage.

“He had a combination of authority and humility which we saw on stage.

“So I kind of expected that.

“What I expected maybe a little less, but I expected it as well, was how funny he was.

“He was very witty. He was quick witted.

“He was sharp although this was the last year of his life, he looked quite frail physically.

“He had lost quite a lot of weight but in spite of that, he was incredibly funny.

“You would laugh whenever you had a conversation with him.

“There would be jokes, there would be witicisms and he was interested in everything: Interested in politics, interested in current affairs, interested in daily life in Los Angeles.

“When I say he looked frail, what really surprised me was how powerful he seemed.

“When you see someone on stage, the great actors, you feel that but he had that in his daily life: A feeling of power and at this stage, strangely enough, I think it had to do with the energy of love. There was something really loving in him.

“He was beaming.

“He was saying goodbye to the world at this stage.

“He knew he was not going to go on stage anymore.

“He knew what he was confronting.

“You never know how long you’re going to survive but he knew the illness was progressing and he wasn’t going to be there much longer.

“But he was deeply in love with life and deeply in love with whatever circumstances arose and you felt that around him,

“I saw him interact with quite a lot of people and it was like he was enjoying every moment.

“He never made you feel that the party was taking place somewhere else.

“If he was just talking on the phone ordering cheeseburgers, this was his life now.

“Or he was talking with me, this was his life now.

“If he was walking down the street, he was really walking down the street.”

Wasn’t he also funny about his illness? There was a great acceptance there, wasn’t there?

“Yeah, I think this irony, this distance is something that had been with him his whole life.

“He developed that sense of humour early: The idea that life is a cosmic joke and that it’s not so much tragedy as comedy.

“Whenever he mentioned his physical condition, he would joke about it.

“My book, as you know, is called The Man Who Saw the Angels Fall and has a lot about gravity in it.

“In his last email to me he says, ‘My body is claiming its rights to gravity very intensely at the moment’.

“It probably means that he was feeling dizzy and couldn’t stand up, couldn’t stay up too long and that was three weeks before he died but he made it sound like a joke.

“He wasn’t clinging. He was enjoying it while it lasted but he wasn’t clinging.

“The last few albums there’s a lot about mortality.

“There’s a lot about how death is not something that just occurs at the end of your life but something that accompanies you and that is like the darkness that will make the light in your life shine brighter, that will make you really enjoy the moments that you spend on this planet.

“Yeah, self deprecation was his middle name and it’s present everywhere in his work.

“I think part of his appeal, actually, is that he mixes a deep sense of the tragedy of life with a constant transformation of that tragedy into comedy.

“And this process is getting more intense as he ages.”

He had a love for Ireland and it all started with an Irish nanny he had as a child, didn’t it?

“Yeah, he located her as a source of his love for Christianity.

“The nanny took this Jewish kid to Catholic churches and she taught him how to light candles.

“We talked about that actually, his love of Catholic churches.

“He wore a bracelet and every bead actually was like a different representation of the virgin.

“I think that’s one of the aspects of Catholicism that he liked and it came from his nanny.

“It’s that Catholicism had this strong presence of the feminine sublime and the strong insistence on love.

“I know for a fact that he also liked the phenomenology of churches, how churches feel: The darkness, the candles, the incense, the sounds.

“This came from childhood and it’s present in the song Suzanne.

“Whenever he was in Europe, whenever he was in a city, he would often stop in churches, light a candle, sit for a while, meditate or whatever, say a prayer and come out.

“It was like going into the sacred world, coming back into the profane world.

“This is something that he did a lot in Paris.

“He loved the churches of Paris and he would chastise French journalists, ‘You should go to your churches. You have got the best churches in the world and you’re not going, go and sit’.

“His love of Ireland was a love of Catholicism. It came from his nanny.

“But I think another strong connection that he had with Ireland was Yeats.

“Whenever he was in concert in Ireland, he would usually mention Yeats and recite a couple of lyrics.

“One expression that he liked a lot was Yeats’ definition of poetry as ‘the rag and bone shop of the heart’.

“And the third connection is music obviously.

“He was deeply moved by Irish pubs, people singing in pubs, and the role that music plays in Ireland.

“I can certainly relate to that.

“The first time I came to Dublin, I was in in this pub O’Donaghue’s.

“You had strong looking men drinking Guinness and suddenly someone started playing a banjo or something, and immediately silence.

“You had all those strong guys with the Guinness singing with tears in their eyes.

“I thought, ‘What a great country’.

“It really runs deep, the love of music.

“I think he was deeply moved by that.

“I was at a concert in Dublin in 2009, and he hadn’t been on stage for 13 years.

“It was in spring but it was very, very, very bad weather so you had a crowd in blue capes and we were all shivering.

“When he sang Hallelujah, I’d never seen it anywhere in Europe but in Dublin, the whole crowd was singing with him: 2,000 people, 3,000 people singing Hallelujah with him.

“After he’d finished the song, he went on his knees to thank the audience and he said, ‘Thank you Ireland for still baffling the world’.

“He knew what a song plays in the cultural imagination of Ireland and how people realise in Ireland how deep a song is, that there is no difference between high poetry and song and that a song will touch your heart in a very deep way.”

You say he admired Yeats, do you know how he felt about Joyce because of course there was that famous quote that compared him to James Joyce..

“Yeah, that was for Beautiful Losers.

“I think it was an American newspaper that said, ‘James Joyce is not dead. He lives in Montreal under the name of Leonard Cohen’.

“His publisher in Canada used it in the publicity then so the quote became famous.

“I know that Leonard had said at least in one interview how honoured he was.

“I know that he liked Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.

“I would say that in his novelistic technique in the first novel, The Favourite Game the way he transcribes the texture of life, the richness of the texture of life, there’s something Joycean probably.”

You spoke of spending time with him and how humble he was. Do you think he realised the profound effect his work had on people such as yourself?

“He has his history of stage fright.

“The first professional concert that he gave, 1967 in New York, he left the stage in the middle of the first song.

“He was just going to play a couple of songs because it was an event organized by Judy Collins but he panicked and left the stage and had to be escorted back onto stage by Judy Collins.

“I think one of the reasons is that he was fully aware what the stakes were when you were an entertainer, he knew that you were not just there to play a couple of songs, that you’re there to reconnect people to their hearts, that the mission is partly to entertain and have people have a good night but it’s also partly a spiritual mission.

“The spiritual mission, as you know, is already contained in his name.

“Cohen is the Hebrew word for priest and he had a strong belief that if you were Cohen, if you carried that name, that was your spiritual mission and you had to serve as an intermediary between people, their hearts and God.

“You had to bring the love of God to people, and you had to bring the love of people to God.

“I think this is how he saw his role as a songwriter.

“If you go on stage, people give you two hours of their time and you have to do something with it.

“You have to make sure that they leave the concert hall being reconnected to something, being reconnected to something bigger than themselves.

“There’s a great documentary called Bird on a Wire and we see that during the tour, he seems depressed and he interrupts some concert. There’s a concert in Jerusalem where he leaves the stage.

“One thing he says in interviews during that tour is, ‘I was not able to give back as much love as I was given by the audience’: This is like a spiritual transaction.

“I think that the last tour that he did went so well that he felt he had accomplished his mission, he felt he had finally nailed it, that he had been a Cohen, that he had risen to the mission that was contained in his name.

“I felt this is one reason why he was so much at peace.

“He felt mission accomplished.”

Leonard Cohen – The Man Who Saw the Angels Fall by Christophe Lebold is available here.